Metal types.

Abu Jar M Akkas

Mr Dwijen, the manager of the printing press in the neighbourhood, is talking to himself. A few steps closer and he is heard murmuring — two hundred sorts of ja with repha (জ-য়ে রেফ), six hundred of anusvar (অনুস্বার), a hundred of mudhanya ṇa with ḍa (মূর্ধন্য ণ-য়ে ড) and two hundred of ka with repha (ক-য়ে রেফ). Mr Dwijen, the character of a short story that Himanish Goswami wrote—‘Puja supplement versus the press’ (পূজা সংখ্যা বনাম প্রেস), is in trouble. He needs all these sorts, pieces of metal types, to print articles written by the communists — ja with repha to print bourgeois (বুর্জোয়া), anusvar to print Peking (পিকিং), murdhanya ṇa with ḍa to print London (লণ্ডন) and ka with repha to print New York (নিউ ইয়র্ক).

He also needs the anusvar sort to print ‘ebang’ (এবং, the word for ‘and’). He still doubts if six hundred of it could be enough. He would also need to print Hong Kong (হংকং) and Yang Si-Kyang (ইয়াং-সিকিয়াং). He might need a thousand of it. If the anusvar sort runs short, he would change ‘ebang’ (এবং) to ‘o’ (ও) or ‘ar’ (আর), the synonyms. The article would certainly have the word ‘bourgeois’, once in three lines, which would make 48 of ja with repha for an octavo of text. He would need to have enough of it to print three to four octavos. He may need two hundred sorts of ja with repha.

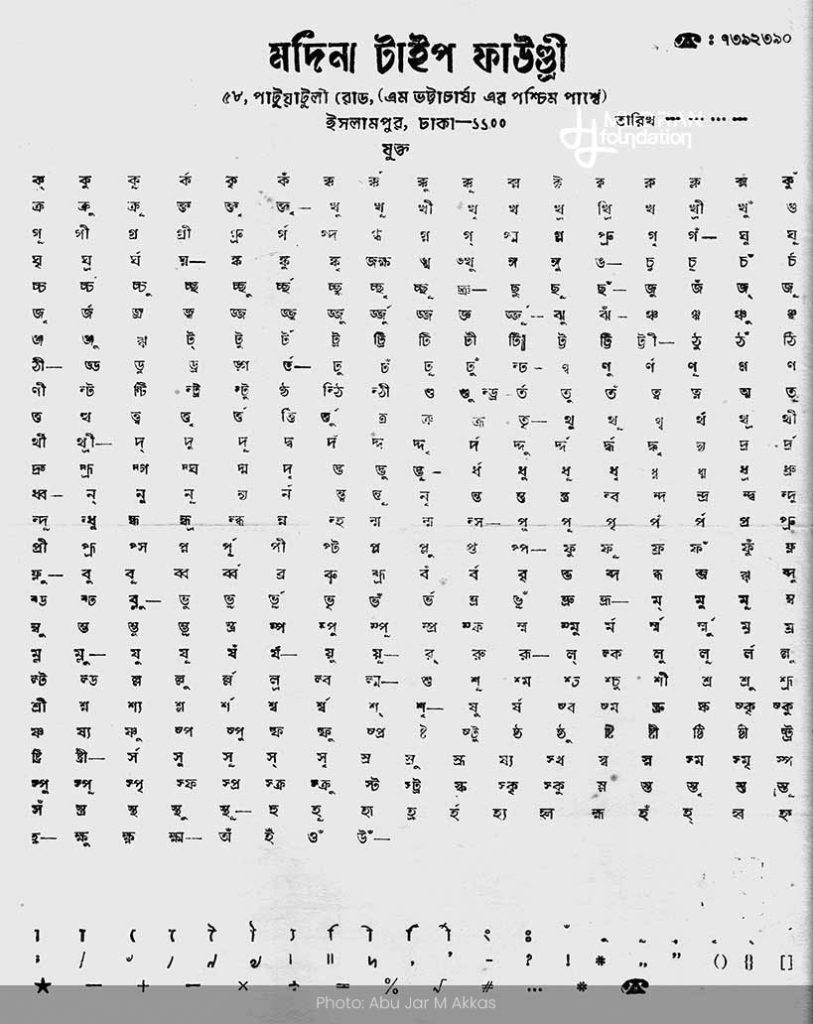

He is rehearsing the count after having bought a set of types. But how would he place the order at the foundry? Foundries those days had sheets of paper with all sorts, or types, printed on them. The photograph here shows one such sheet from the papers of a foundry in Old Town of Dhaka, Madina Type Foundry, which ran at Patuatuly. This was one of the three still doing business by the turn of the century. A circle would be drawn around the individual sort and the requirement would be written, by the number or the weight needed. It would take a few days for an order to be processed. The processing time came down significantly in the dying days of printing with metal types, when the foundries had a couple of customers a day.

After the foundries would receive the orders, one or two of the employees would enter the store. They were mostly all alike, like the foundries. A few steps past inside the door to Madina, with a sign overhead, the room is lighted to the need — a table, with a ceiling fan turning over the head with some noise, a telephone on the table and a registry book to keep count of the sales. There would be a type specimen book or two, with printed samples of all typefaces available, the names and their size — Ganabangla 18pt, Pica 12pt or Rupashri 24pt. Buyers, basically print shop people, would order types after choosing faces from the specimen book.

Metal types fell into disuse. Foundries became useless. The days of the trade, and technology, of printing with metal types ended.

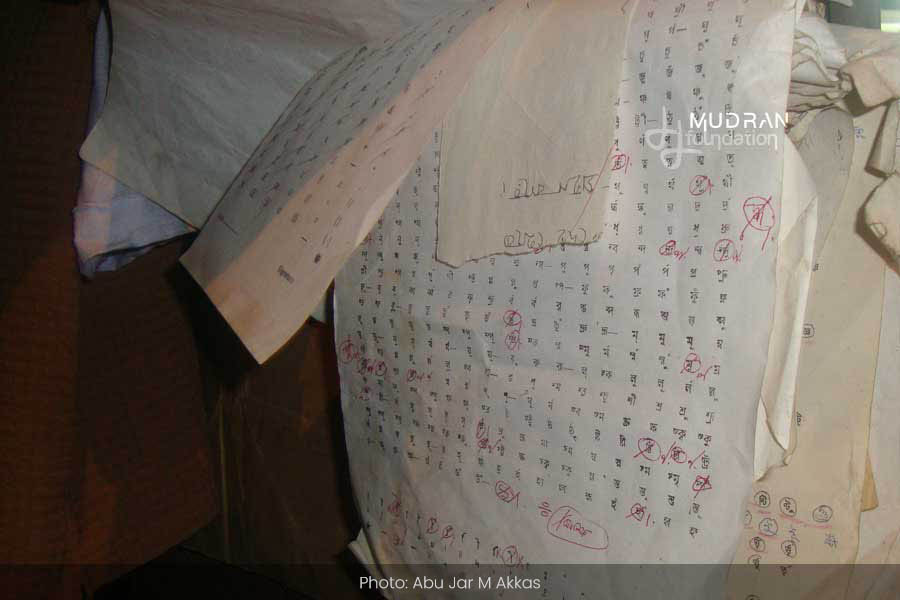

In most type foundries, the places where types were cast and stored were adjacent, as it was the case with Madina, a few steps outside the other door through the office room. There would be rows of racks, leaving room in between enough for someone to move. Some of the racks had drawers. There could be a ladder to reach the upper shelves. The shelves would hold cones made of paper from cement bags, each with one sort of the face and the size written on it. Inside were the individual lead sorts of that size. An employee would climb the ladder and find out the cones needed and another would weigh the sorts if the order was given by weight and count them if the order was by number. The accompanying photograph gives a glimpse into what the store of the Madina foundry looked like. The foundry closed down a few years later. Metal types fell into disuse. Foundries became useless. The days of the trade, and technology, of printing with metal types ended.

Abu Jar M Akkas, a journalist in Dhaka, is a linguistics and typography hobbyist.